The present state of Thailand

While putting together his first eBook, an anthology of his short stories, Pira Sudham carried out research into where Thailand now finds itself. Below are his notes for It is the People of Thailand and Other Countries.

The Author’s Notes

Deforestation.

Due to relentless efforts to secure vast areas to grow eucalyptus trees in order to meet the demand for woodchips and pulp from the paper and packaging industry in and outside Thailand, parts of lush rainforests, national parks, forest reserves and arable farmlands have been sacrificed. The calamity brought about by the eviction of more than five million people out of their holdings became paramount when the affected people appeared in great number in Bangkok to plead for help from the government.

Attempts to save the remains of the forests have brought to light the conflict between the will of conservationists and the power of the state that determines to make such sacrifice.

Similar to Kaoko in Petchaboon during the war against the insurgents in the 1970s, Huanamput Forest in southern Burirum became a battle ground between the military and the guerrillas. Bullet marks in tree trunks still bear witness to its brutal past. Then, in the 90s, another kind of war took place. An elderly Buddhist priest, Pra Prajak Kutajitto, and a band of Pakam villagers fought to protect the last patch of the forest against illegal logging and influential land speculators.

Abundant with wildlife, Huanamput Forest stretches over 20,000 rais (8,000 acres), a source of five rivers in Burirum. The military strategy to deprive the insurgents of their hiding places destroyed vast areas of this forest reserve.

Pra Prajak came to Huanamput in 1988, the year in which the Department of Forestry was evicting small holders out of the areas declared ‘degraded’. By classifying the forest reserves ‘degraded’, the woods could then be replaced by eucalyptus tree planting under the so-called Reforestation Scheme.

Being anxious that the forest would be logged and then be classified as ‘degraded’ in few years, Pra Prajak declared Huanamput Forest a sanctuary and led his followers to start the conversation work.

Already eager to find ways to protect the remain of the forest, the villagers living in 25 villages near Huanamput came to help the conservationist monk, marking the beginning of the alliance between the monks and the inhabitants, particularly among the men who had already formed a conservation group in 1989 to curb illegal logging.

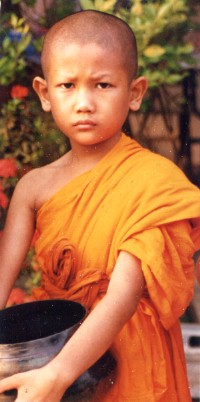

Both the monk and the laymen were aware that conservation work could turn perilous. The yellow robes could hardly protect them against bullets. Still they worked on, organizing surveillance teams, keeping watch on poaching and logging. They blocked the roads that illegal loggers used to transport timber out of the forest.

“One night somebody fired shots at short interval for over half an hour some five metres from my shelter,” Pra Prajak said. ”Next morning I found a message pinned to a board in the sala, saying: If you do not leave, we will be back to kill you.

When threats and various forms of intimidation did not work, a gang of local officials and armed men paid Pra Prajak a hostile visit, ordering him and his followers to pack and leave.

“Thailand is supposed to be a Buddhist country, but if they can vilely treat a senior monk, we can guess what they will do to us,” one village leader said.

In 1991, Pichit Sukhothai, a senior official of the Department of Forestry, lodged a complaint with the local police, accusing Pra Prajak and 20 conservationists of encroaching on a forest reserve.

A Burirum court gave the monk a two-year sentence. But the case against the laymen dragged on with no end in sight, causing the accused to go to the court two or three times a month.

While the accused laymen were in the throes of court cases, some armed men visited the villagers, promising to drop the charges if they agreed to disassociate themselves from Pra Prajak.

On 16th September 1991, Bangkok Post commented in its Post Opinion column: “The Conservation Award granted to the Pa Kham Villagers of Buri Ram last year by the Siam Environment Club was in recognition of their selfless dedication to protect the Hua Nam Phud Mountain, reputed to be the last rainforest in the province. Covering only about 20,000 rais, the densely-forested mountain is the source of five rivers in Buri Ram.

“While the efforts of these self-appointed grass root conservationists won widespread commendation from a host of environment groups sadly their efforts have gone unacknowledged by state authorities. This is particularly so in the case of the Forestry Department which has always complained of a lack of funds and manpower to police the country’s forests against illegal logging. Instead of winning official appreciation, the environment-conscious villagers of Pa Kham have found the bureaucrats to be as strong adversaries as illegal loggers and land speculators and agro-industry corporations, all of whom seem eager to strip the mountain bare of its trees and to turn it into commercial plantation.

“The conflict of interests between the Pa Kham villagers who want to stay on to protect the forest, the source of their livelihood, and local forestry officials determined to undertake commercial reforestation has led to a number of violent incidents over the past several years.

“The heavy-handed treatments by military authorities of the villagers and their spiritual leader Pra Prajak Kuttachitto, a policy that has chosen to overlook the military’ own involvement in the initial ‘encroachment’ makes the villagers seem like sacrificial lambs who can be disposed of when they no longer serve the objectives of the military. The use of military men to forcibly evict the determined villagers not only casts a negative light over the military as a whole, but also raises questions about double-standard treatments.

“It is a fact that large tracts of forest reserves have been illegally acquired, stripped bare of forest cover and turned into resorts or golf courses by influential people with high-placed connections in military or government circles. With the exception of a few developers who are facing legal action, most are likely to escape scot free and enjoy the benefits of the rape of our forests. They certainly seem unlikely to receive harsh treatment from the military.

“Now with the Pa Kham villagers separated by divide-and-rule tactics to break their resistance, the chance of the villagers defying eviction appears doomed. Responsibility to safeguard the Dong Yai forest and Hua Nam Phud mountain is therefore likely to be transferred to the hands of the Forestry Department.

“Given the department’s record of zealous pursuit of commercial reforestation, one wonders whether the department will be able to resist the temptation of the commercial benefits to be gained from transforming this last natural heritage of Buri Ram into a huge eucalyptus plantation for corporate interests.”

At this time, a letter to The Editor of Bangkok Post appeared in the Post Bag section. It reads:

I’m disturbed to hear of military action against farmers in Pa Kham District of Buri Ram following last week’s military take-over. The villagers of Pa Kham are famous for their efforts to protect the natural forest of Dong Yai against illegal loggers and to replant degraded areas with locally useful tree species. For years they have resisted efforts by local profiteers and officials to take away their lands, destroy its forests, and turn it into eucalyptus plantations benefiting only a few.

Something would appear to be seriously awry when a quarter of a country’s people are technically subject to violent eviction from their homes; when villagers internationally recognized for their conservationist activities are being accused of forest destruction by loggers and plantation interests; and when a junta which has pledged to curb corruption creates a climate in which ordinary people can be victimized so easily by the wealthy.

Pace George Bush, a conflict over resources such as has emerged in Pa Kham is not going to be solved by throwing guns and soldiers at it.

Larry Lohmann

Larry Lohmann spent much of the 1980s working with voluntary organizations in Thailand on social and environmental issues. He is the co-author (with Ricardo Carrere) of Pulping the South, Industrial Tree Plantations and the World Paper Economy, published by Zed Books Ltd (London) in 1996. He is also the co-editor of The Struggle for Land and the Fate of the Forests (Zed Books, 1993).

As soon as the eviction of the inhabitants began, several large nurseries were built to propagate eucalyptus seedling from seed imported from Australia. Then the planting followed after the areas were cleared of trees and the dwellers’ cash crop which were mainly tapioca.

On 16th March 1988, over 2,000 evicted people convened to seek help from the government to solve the problems of land conflicts and the destruction of their crop, but to no avail.

Eucalyptus planting increased rapidly and the plantations expanded over the arable lands previously used by the villagers. Not only ignoring the villagers’ complaint, the authorities concerned considered that planting eucalyptus trees was more important than the people’s cash crop and their livelihood.

The villagers protested against the eucalyptus planting by cutting down 200,000 saplings on 20 rais and burnt two nurseries. The authorities claimed that the damage caused by the revolting villagers amounted to 11 million baht, and the culprits must be punished.

Kam Bootsi and 23 village leaders were arrested.

“They are not only after greater areas of forests but also the timber,” Pra Prajak warned. “After big trees are logged and sold, they will plant eucalyptus trees. It has happened in many parts of the country.”

When the conservationist monk did not relent, his opponents filed a petition with the provincial monastic chief to order their obstacle to leave the forest and if possible to disrobe him. The Buddhist sanctuary, they claimed, was an encroachment on the forest reserve and the shelters were made of wood logged from the forest reserve.

The temple in the sanctuary had only a few rudimentary shacks made of bamboo and thatched with plastic sheets. The biggest building was the hall or sala, an open shelter for meditation and prayers.

After an investigation, the monastic chief announced that the sanctuary and Pra Prajak’s presence helped preserve the forest.

Having failed to drive Pra Prajak out of priesthood, the authorities atrociously attacked the monk and the conservationists, arresting the meddlesome priest and 23 laymen. The charge was trespassing.

Out of jail after the two-year imprisonment, Pra Prajak directed his followers to plant more trees in and around the sanctuary, inviting also conservationists and environmentalists from other parts of Thailand to visit Huanamput.

“The preservation of the forest is significant in the practice of Buddhism,” the conservationist monk said. “One thing that the authorities can do to help is doing their duties, leading us in preserving the forests and by being less corrupt and avaricious. Though bribery, our forests are sold to influential men in the form of granting concessions. Those in the seat of power to ‘grant concessions’ to individuals or commercial concerns are in fact instruments that destroy the woods, turning the remaining forest reserves into commercial eucalyptus plantations and, in some cases, into golf courses and resorts.

“The Department of Forestry’s handing over 235 rais of forest reserve in Huykaew District in Chiangmai to a Mrs Pramern Shinawatra is a case in point. Alas, Nid Chaiwanna, teacher of Ban Huaykaew School, was shot dead on 15th December 1989 by professional gunmen while he was leading a band of demonstrators, protesting against the Forestry Department’s granting of concession to the Shinawatra family. How many more conservationists and environmental activists have to die before they realize that the destruction of the woods and the pollution of the rivers are beyond redemption?”

Eviction of small holders in areas designated for eucalyptus planting too is another drastic drive being carried out by the authorities. In the past decade over five million people have been evicted. In some cases, the evictions turned bloody and brutal, causing also waves of homeless migrants to drift towards Bangkok.

In April 1992, about 500 inhabitants in Kutbak and Pananikom districts of Sakonnakorn Province convened for the fifth time to air their grievances caused by forced ‘relocation’ under the government’s new land resettlement scheme.

“This scheme is designed by the powerful to evict us from our ancestral lands to make way for investors to plant eucalyptus,” said a village leader. “They go against social reality. The army bullies the ordinary folk. They did not spare even the Buddhist monks.

“We have lived here for generations, and suddenly they want to removed us from our birthplace and relocate us in a barren and infertile land,” said a village elder.

“The Prime Minister General Suchinda Krapryoon and Army Chief Issarapong Noonpakdi have never tasted poverty. They do not understand the feelings of the poor and the powerless,” said another village elder.

Some of the grievance makers said that General Suchinda and General Issarapong acted as though the country belongs to only the two of them.

Their outcries were futile. However, in less than a month, the karma caught up with the two most powerful men in the Kingdom. They lost their seats of power after having massacres hundred of pro-democracy marchers in May 1992.

As a whole, the authorities or as the rural poor call them Nai (Masters) view the people of the lower orders, the peasants and rural poor as being sub-human to be kept in suppression, in a voiceless and powerless state. But when the suppressed people had group strength and dare enough to make outcries, they were seen as hooligans or mobsters or having been paid by a certain group of people to make troubles.

By then the total of 9.2 million rais of the so-called ‘degraded’ forest reserves in Burirum, Nakornrajasima, Sisaket, Surin, Yasothorn, Petchaboon, Udon, Sakolnakorn and Ubol have been granted to eucalyptus plantation companies.

Injustice

The self-imposed task of safeguarding Burirum’s forest reserves kept Kam Bootsi alive. He had been hailed as a grass root conservationist. But as far as the authorities are concerned, he had been on top the wanted list. His name was underlined in red ink. Pra Prajak’s name was also on this list.

Early one morning in January 1991, more than 100 policemen stormed villages in Pakam District. They arrested 67 members of the Pakam Forest Conservation Group.

Kam, who was 43 years old in 1991, escaped but was later captured and jailed.

“The people who are trying to protect the forest are being brutally treated like criminals. Fully armed, they attacked us as if we were guilty of serious crimes,” said Kam, who had to face 11 charges. “Fifteen years ago, when the military wanted to destroy the insurgents’ strongholds, villagers were encouraged to move in and cut down trees and clear the forests and grow cassava, following the government’s cash crop promotion for exports. So we did, but now they want us to clear off so as to make ways for concessionaires and their eucalyptus trees,” said Kam.

In all, Esarn lost over 5,000 square kilometers of forests or 3.2 million rais at the height of the war with the insurgents between 1976 and 1978. The military set up head-hunting units against the guerillas, and Kam was the leader of such a unit.

“I have grown accustomed to fighting. I am used to living with anxiety and tension,” he said when asked about death threats from illegal loggers and his difficult relationship with the authorities.

When the guerrilla warfare came to an end, only 20,000 rais of forests remained. Thailand’s forest reserves have rapidly dwindled from 62 per cent in 1950 to 15 per cent at the end of the 20th century.

The Japanese were eager to import logs, woodchips and pulp from Thailand, and investors were in a rush to establish a pulp and paper industry here, resulting in the urgent need for vast areas of land, where fast growing eucalyptus trees could be planted. In Esarn alone, over 300,000 families were moved out of the wanted lands to make way for eucalyptus plantation companies which had obtained the concessions from the Department of Forestry.

There are over one million families living in areas which the Department of Forestry wanted to regain, and the drastic commercial tree planting policy has given rise to using armed men to force eviction. Ceaseless eruption of land conflicts have ensued. What set Pakam villagers apart is their particularly vehement and well-orchestrated resistance, the skills they learnt during the guerrilla warfare.

The effort gained the Pakam village leaders a conservation award from the Siam Environment Club in 1990. If the award could become a powerful tool to the unarmed villagers, it might mean that the billion baht eucalyptus plantation businesses would be halted; land speculation which is growing in Pakam would face obstacles; illegal logging activities which provide briberies to many levels of the authorities would also be disrupted. So, too, many state programmes which require the use of lands already occupied by villagers would be aborted.

“We are in the way of too many powerful people,” Kam said on 21st January 1991. “That is why we cannot be spared.”

On 10th April 1991, Pra Prajak Kutajitto, Kam Bootsi, Tas Raksanoi, Thongsai Namviset, Boon Tongthep and Nikom Pongsicharoensuk were arrested.

For conservation activities, Pra Prajak and his followers faced legal charges including trespassing, forest encroachment and disruption of public peace. Fighting alone with little support from outside, the leader soon became exhausted by time-consuming, costly legal battles as well as several threats on his life.

Defeated and desperate to regain his freedom, the accused conservationist monk made an escape in 1994 and disrobed after 17 years in the priesthood. In hiding, he went under a layman’s name of Prajak Petchsingha. He was re-arrested in 1995. A group of friends bailed him out later on. Well-known social critic Sulak Sivaraksa offered shelter to the fugitive at Wongsanit Ashram, a sanctuary and a meditation centre, of which he was a founder, in Nakornayok Province.

Prajak lacked the knowledge of how to deal with the authorities’ ploy to wear him down in a long-drawn out court cases against him. With five pending court cases, the former conservationist monk must go three times a month to the court. Worse still, the beleaguered man has been plagued with mental exhaustion.

“I lost my spiritual strength the day I disrobed, and now my mind has grown weak,” he admitted.

Physically, he was still active, making himself useful at the Ashram. Dharma practice was still part of Prajak’s everyday life. He rose at 4 a.m. to pray and meditate.

“But deep in my mind, I feel uneasy. I cannot help worrying. I worry a lot about the trees in Huanamput now that they have no one to protect them from chainsaws.”

Asked if he would like to return to the priesthood, Prajak Petchsingha, who has recently made it to his 60th birthday, said that the sooner he could re-enter priesthood, the happier he would be.

By then Dongyai, the last patch of rain forest in southern Burirum, had succumbed to illegal loggers and land speculators.

On 11th May 1995 the court sentenced Kam Bootsi and Boon Tongthep to three years in prison.

“Being in and out of jail does not worry me, but I mind very much that the authorities acted as if we were criminals when we tried to protect the forest reserve for younger generations,” he lamented. “The illegal logging increases all the time. How many trees would be left standing in Dongyai while we languor in jail.”

Over 20 members of the Pakam Conservation Group were lined up to face court cases on similar charges. Kam fought against seven charges and lost. The loser was to be driven deep into the ground after having done his time in jail.

“He is lucky,” said one of Kam’s fellow conservationists. “It could have been worse. Usually bullets work faster. Look at Nid Chaiwanna of Ban Huaykaew in Chiangmai. He did not have chance to cry for help.”

The winners had the blessings from the Department of Forestry (known among conservationists as Krom Tumlai Pamai -- the Ministry of Forestry Destruction) to gain more tracts of land in and around Dongyai to log the forest and to clear the so-called ‘degraded’ land and plant eucalyptus trees. Soon Dongyai, which means Big Forest, would be known as Dongnoi, Small Forest, or Dong Euca, Eucalyptus Forest.

Meanwhile, the inhabitants in Banpue District, Udon, did not understand why indigenous trees in the nearby forest had to be logged and replaced with eucalyptus. It happened in June 1994 when Mr Prasit, an official of Banpue District came and rounded up 300 local men and women. He wanted them to cooperate in the reforestation scheme, with an order that came down from the Ministry of Agriculture to commemorate His Majesty’s 50 years of ascension to the throne.

“The villagers had no idea what such reforestation project was all about, but for the love of the King, all happily complied,” said Boonrod Khunkaew, headman of Kaosan Village.

A few days after the meeting, a team of men with chainsaws and three bulldozers arrived at the forest and began clearing the land of precious trees that have thrived there for centuries. Villagers also saw several ten-wheelers to transport the logs supposedly to some saw mills. In a week, 600 rais of land was bare and ready for ‘reforestation’.

“It was a big event,” said Boonrod Khunkaew. “The district chief came to preside over the ceremony. The district forestry officials and agricultural officials and other important officials also attended the opening of tree planting ceremony.

More than 300 villagers volunteered to take part in the planting. But to their dismay, the saplings given to them to grow were eucalyptus. Soon they realized the loss of common native woodland to commercial tree planting.

“It is a pity that our natural forest was wiped out for planting eucalyptus,” said village elder Chom Thanachai. “Now not a single mushroom and wild life could be found there. We do not have any woods left to forage for food. ”

Chom said also that he would prefer to see other species of trees planted there instead of 100 per cent eucalyptus. Worse still, 50 rais of adjacent forest land traditionally reserved as a place for cremating and burying the dead was cleared and turned into eucalyptus plantation as well.

“Now we do not have a natural place to cremate or bury our dead,” he said.

Why eucalyptus trees are more important than the livelihood and the survival of the people?

This tree species, native of Australia, is fast growing. The trees can be harvested after 4-5 years of growing. It thrives well on arid land as well as wet land. It means that the growers could make fast returns as eucalyptus woodchips are in great demand by pulp and paper factories in and outside Thailand.

But what the authorities did not take into consideration is the adverse effects this tree variety has on the ecology. For instance, the soil becomes infertile after few years of growing eucalyptus; the ground water is quickly depleted since the trees consume a huge amount of water to grow fast in a short time.

Due to aridity in the soil and in the air, precipitating point that brings about rainfalls can hardly be reached. Drought ensues. Like Australia, Esarn is facing more and severer drought problems than before as a result.

Besides, after few years of their growth, grass and other plants cannot survive underneath eucalyptus trees due to desiccation and acidity. The latter derived from rotten eucalyptus leaves fallen all round, a self-protecting and generating way so that only eucalyptus can grow among themselves.

The inhabitants, who realized the harm eucalyptus could do, named it the selfish tree variety.

A soil expert claimed that it might take 20-30 years to repair the damaged soil where eucalyptus trees were grown.

To observe from the roads, samples of successful eviction and the triumph of eucalyptus planting over the suppressed people and native trees, take Route 359 that links Highway 304 with 33 in Sakaew Province, and Route 3393, 3486 and 348 to Nondindaeng and Pakam.

When all else failed, in October 1991, over 60 villagers, facing eviction from their holdings designated for eucalyptus planting in seven Isan provinces, turned up in Bangkok to petition His Majesty the King. They begged not to be evicted. The petition signed by villagers in Burirum, Nakornrachasima, Sisaket, Surin, Yasothorn, Kalasin and Ubol alleged that the real purpose of the reforestation scheme was to hand over 10 million rais of arable land to commercial eucalyptus planting. The petition also pertained to the military action to destroy 100 rais of tapioca in Soengsang District, Korat, in an attempt to force the people to move out of the area.

Corruption

Recognized as one of the top ten most corrupt countries in Asia and one of the 50 most corrupt in the world, Thailand has been plagued with corruption to a degree that the cancerous growth has reached the core. Venality has also been accepted as a way of life, in daily routine or in commercial enterprises, so that briberies and kick-back takings have been in practice to achieve the desired results whether they are in granting and winning concessions, licenses, bids, monopoly, and permission to develop certain industries and projects.

In 1885, A. R. Colquhoun recorded in Siamese Life and Customs as follows:

The impression which most travelers in Siam have received in regard to the moral characteristics of the people has been generally favorable and is on the whole confirmed by the judgment of foreigners who have been longer resident among them. They have, of course, the defects and vices which are to be expected in a half savage people, governed through many generations by the capricious tyranny of an Oriental despotism. And the climate and natural conditions of the country are not suited to develop in them the hardier and nobler virtues. Industry and self-sacrifice can hardly be looked for as characteristics of people to whom nature is so bountiful as to require of them no exertion to provide either food or raiment. And on the other hand, with the sloth and inactivity to which nature invites, the animal passions, by indulgence, often become fierce and overmastering. But it seems to be agreed that if the Siamese lack the industry and economy of their neighbors the Chinese, they have not the passionate and sometimes treacherous character of the Malays.

It is more or less true of Thailand today. Though the country has changed its name, the mentality and attitudes of the people have not altered much. The difference is that present-day foreign observers including foreign correspondents dare neither air nor print their keen observations while residing in the Kingdom, having seen what happened to the two correspondents of the banned (and later collapsed) Hong Kong based Far Eastern Economic Review. The grants of their working permits and visas are at the whim of our despotic leaders.

As far as the conflicts and tensions caused by deforestation are concerned, corruption plays a vital role in the destruction of Thailand’s forests.

Corrupt government officials are becoming more avaricious and cunning, according to Counter Corruption Commission Secretary-General Prasit Damrongchai. “The more power they have, the richer they become due the abuse of their high positions and power to accumulate great wealth as quickly as possible. Along the way they have developed complicated tactics,” he said.

The most common form of graft among government officials is acceptance of bribes, followed by the abuse of power, using one’s high ranking position for greater personal gain.

“Corruption widened with the advent of large ‘Projects’ that required government endorsement,” said Prasit Damrongchai.

“For example, officials receive bribes through playing golf for high stakes and millions of baht was bet on each hole,” he said. “The bribers always lose their games. Another way is top officials and military leaders take part in developing real estate or golf courses, and then sell the properties to private operators at extraordinary high prices.”

Said to have lost two million baht at a game of golf, a prominent member of parliament gained a ministerial post. Apart from turning a blind eye on illegal logging, he got hold of a vast area that once was part of a forest to turn into vineyards. He had also assisted a pulp and paper firm of which he became Chairman to become the largest land owner in the Kingdom.

The eucalyptus plantation company concerned was given concessions to eight sections of ‘degraded’ forest lands totaling 8,750 rais (3,500 acres) for planting eucalyptus. Its workers moved in on the ninth section before a permit was issued. The workers were also seen encroaching on 2,000 rais of the adjacent forest, enabling the company to gain control of more than 3,000 rais of forest reserves without permission. And the said minister could not see any wrong doing being committed by the said company.

Under the original government policy, the so-called ‘degraded’ forests can be sold to concessionaires for bona fide projects, mostly eucalyptus planting. But any application for more than 2,000 rais of the degraded forest requires approval from the government.

The company circumvented this regulation by applying for fewer than 2,000 rais for each lease. This enabled the minister to approve the applications.

The said minister claimed that he did not see anything wrong in the company’s tactics either, asserting that the firm was a legitimate investment which corresponded with the government’s policy of increasing commercial forests to cover 40 per cent of the country’s arable areas, a target set by the government.

Turning a blind eye to encroachment on forest reserves and national parks as well as on illegal logging greatly enriched the minister and his corrupt high-ranking officials involved.

The killing of conservationist Nid Chaiwanna, teacher of Ban Huaykaew School in Huaykaew District of Chiangmai on 15th December 1989 highlighted another case of how an influential individual or a company could own vast areas of forests or public lands.

In response to an application for land under the reforestation scheme, the Department of Forestry granted Mrs Pramern Shinawatra, 235 rias of a ‘degraded’ forest reserve in Huaykaew District of Chiangmai.

There were rumours that the reforestation project was a façade for an estate development project.

Against this concession, villagers living in Huaykaew District petitioned the governor of Chiangmai, Dr Pairat Decharin, as well as Prime Minister Chatchai Choonhawan, but to no avail.

In July, Kasetsart University students surveyed the area and concluded that the 235 rias of forest land was not degraded. Moreover, the concessionaire had encroached on forest reserves in proximity of the permitted area.

These findings were confirmed in September by a second survey team of the Counter Corruption Commission, which ruled that the concessionaire had encroached on 140 rais of additional rain forest that remained above the ‘degraded’ status.

The conflict recurred on 14th December when conservationists Nid, Thawisin and Chiangmai university activist Vichien were arrested after having been charged by Pramern Shinawatra of damaging her property and trespassing.

Nid Chaiwanna was shot dead by hired gunmen the next day. His brutal death sparked massive protest and hunger strike. Protesters demanded that the Shinawatra concession be revoked.

Certain official documents indicated that the Shinawatra’s concession was never revoked and the concessionaire resumed the ‘project’ without further hindrances.

In October 1991 some 2,000 men and women from Isan (northeastern provinces) namely Ubol, Sisaket, Surin, Korat, Chaiyapume, Khonkaen and Udon reached Bangkok to plead the government to help solve their problems brought about by eviction from their lands wanted for dam construction and eucalyptus planting and for other state development projects.

Since the mass gathering of unarmed villagers looked peaceful enough, the police force did not use violent means to disperse the crowd. Instead the pleading people were persuaded to return to their villages since their rally in Bangkok caused traffic chaos and an unnecessary nuisance. Moreover, the ugly sight of despicable peasants in the capital might tarnish the country’s good image. In some quarters, the shameful presence of the suffering poor was seen as being a political tool to benefit certain ‘trouble makers’.

“I shall stay put here in front of the Government House until someone in authority tells me that I can have my land back,” said 80-year old Tim Nonsoongnern from Sikew.

One of the hundreds of families unjustly evicted from their lands, Tim claimed that the confiscated 10 rais were her ancestral farmland. “I was born and grew up there and I want to be buried there,” she said.

Despite physical discomfort, without sufficient food and water, sitting under the sun and the rain in daytime and being bitten by mosquitoes at night, Tim Nonsoongnern and the thousands of ‘protestors’ could not be easily dispersed.

“I will not go back home until some people in authority make a firm promise that I would have my land back,” said Tim.

“Being in jail is like being in hell,” said the former Buddhist monk, Jirapan Jaikla in Surin jail, on 20th March 1990. His surname, Jaikla means brave heart.

In early March, the monk was disrobed and arrested so as to enable the military to charge Jirapan with encroachment on the land on which the Jaiklas had lived for generations.

His impoverished 71-year old mother, Am Jaikla, could not raise 40,000 baht to bail him out.

Before becoming a Buddhist priest, Jirapan lived with his widowed mother, toiling on 30 rais of farmland in Ban Taan, one of five small villages three kilometers from the provincial town of Surin, where the military had claimed the ownership of their farmlands.

The evicted householders said they had lived on their farms for three generations. To make their grievances known they gathered on 26th February and rallied in front of Surin Town Hall

A squadron of armed men made atrocious attacks on the protesters in the presence of the military personnel and the police.

Jirapan, the priest, was there, trying to protect his ageing mother from being brutally battered. As a Buddhist monk, he must not be in bodily contact with females. Therefore, to avoid touching his mother in protecting her from harm, he stood between her and her assailants. In so doing he was seen as a leader of the mob, obstructing the armed men from their duty which was bashing and battering and clobbering and stomping on the revolting peasants.

Jirapan was arrested and charged.

“I was also seen as the spiritual leader of the villagers in trouble, and as long as I am a monk residing at the monastery in the village, the military considered that I was preventing them from suppressing the people,” said the prisoner. He also claimed that while the people of Ban Taan were being battered and stomped on by armed men wearing army boots in front of Surin Town Hall, a tractor was demolishing Ban Taan Monastery.

“If the military can do that to a place of worship and a sanctuary of Buddhist monks, they can do anything, including murder, to ordinary and unarmed people,” he said.

Jirapan’s remark proved to be correct. Thai military forces massacred thousands of pro-democracy marchers in the streets of Bangkok on the 14th October 1973 and on the 6th October 1976 and the 18th-20th May 1992. Perhaps another series of massacres are yet to follow. (These massacres were recorded in details in Pira Sudham’s Shadowed Country.)

The tensions brought about by land conflicts with the mighty put a spotlight on brave-hearted Jirapan Jaikla’s life.

Before he became a monk in 1988, he led a simple peasant’s live, tilling his farmland along side his parents. To improve their living condition, he bought a cow for propagation from a government agency on installments. Then his father died and later Jirapan broke a leg in an accident. Being disabled, he could not take on heavy tasks. As a result, he opted for priesthood, residing at Wat Ban Taan with four novices.

An eyewitness, Prayune Kaewdecha, 40, a dweller of Ban Taan, claimed that he saw several soldiers, during the demolition of Ban Taan Monastery, take sacred Buddha images and cash, which the villagers had donated to the monastery, away with them after they have demolished the buildings.

“Our village existed in the eye of the law in 1914,” said Prayune. “The military staked its claim over our lands in 1941. In 1969, the military took our group leader, Yone Yuangtong, to court, charging him with encroaching upon the army land. The court dismissed the lawsuit on the ground that the inhabitants had lived there a long time. This time, it sought forceful eviction instead of the court of law.”

The Long Marches

The evictions of over 500,000 people from their properties, which would be submerged after the construction of huge dams were completed, exacerbated the tensions created by the evictions of over five million inhabitants from areas designated for planting eucalyptus. On top of all the conflicts brought about by evictions, the suppression of agricultural produce too augmented the tensions which were reaching a breaking point.

The construction of the 136 megawatt hydro-electric Moonmouth Dam in Ubol in 1991 is a case in point.

It is a case of development taking priority over ecological balance and livelihood of the people. When completed, the US$100 million World Bank sponsored Moonmouth Dam proved to be a failure. It failed to generate sufficient electricity as projected at the unfathomable cost of human sufferings and ecological disaster.

The brutally evicted people were mostly small holders of farmland, barely literate and seen as being the underclass and easily subjugated. Most of them could not speak the Thai language and had never heard of human rights.

In 1994, the seemingly meek and tractable peasants rose in their thousands to protest against the unfair, and in some cases brutal treatments.

The Electricity Generating Authority of Thailand (EGAT) tried to ‘sweep the problem under the carpet’ by using all kinds of tactics, but the protesters’ desperation and the will to survive urged them on. It seemed that their will could not be easily broken.

However, their pleas were seen as their demands for money when opportunities occurred. The authority seemed to have closed its eyes on what caused the suffering people to plead for help.

Apart from the loss of vast areas of farmlands, the Moonmouth Dam caused the destruction of the fish ecology of the Moon-Mekong river flow, therefore affecting the food foraging and income source of the people, particularly the fishermen whose livelihood depended on them. But the EGAT chose to ignore them.

On the other hand, those evicted families were relocated at new sites not viable for farming and vegetable growing due to poor soil and drought. The new lands that replaced their arable farmlands were suitable only for building houses on and not for tilling. To survive the relocated people had to change their livelihood from farming to becoming labourers for hire.

Hence, the majority of the relocated people migrated to Bangkok and some other large cities for employment.

In their plea for compensation for the loss of food and income from fishery, the affected people calculated that their daily income from fishing at the Moon River is 100 baht. The EGAT yielded only 9.50 baht a day for each family. In total, each of the affected 1,165 families received 10,000 baht and 300 families got slightly higher than 10,000 baht.

The EGAT stood its ground of not giving more to all of the pleas for fair compensation. As a result the protests grew in number from day to day, week to week, month to month and year to year for seven years. The authorities seemed to take an easy way out by considering that the protests were made by trouble-makers, the hooligans and the paid mobsters. In some of the clashes with the so-called paid mobs and hooligans, violence occurred.

The World Bank’s senior official from Washington admitted that apart from being a failure, the Moonmouth Dam was a mistake.

Yet, the World Bank, which was supposed to share the responsibility with The EGAT, remained silent despite its policy to take into account environmental concerns when granting loans for large-scale projects. In fact, the Bank had coined a catch-phrase in its lending policy: ‘People shall be better off or at least no worse-off’.

In later years, the World Bank, went ahead to sponsor a huge hydro-electric dam in Lao.

The EGAT’s relationship with the World Bank began over three decades ago, resulting in the constructions of several huge hydro-electric dams in Thailand, and the state agency had been selling electricity generated from these large dams at great profits. Yet The EGAT insisted on refusing to give up a tiny slice of its annual profits to settle the Moonmouth Dam conflict. It did not even want to lift the legal complaints filed against 13 students and villagers who set off the protest.

In all the Moonmouth Dam movement has become a symbol of the struggle of the powerless people against the powerful.

“The EGAT makes over seven billion baths each year. At least it can easily give a total of 200 million baht to make up for the losses of the affected people’s farms and livelihood,” said Pisit na Pattaloong of the Wildlife Funds of Thailand.

“The Moonmouth Dam protest is a prime example of a non-violent people movement in Thailand. But The EGAT has forced the suffering people into a corner by deliberately ignoring their sufferings and their pleas for help and for fair compensation,” said Bamroong Kayotha of the Small Scale Farmers Group.

On 14th December 1994, a letter to editor of The Nation appeared. It reads:

I never intended to take part in the public debate about the Pak Moon Dam (Moonmouth Dam). However, when I see that the protesting villagers are branded as hooligans and mobsters, I feel a compelling urge to protest. They may be unschooled and simple, but they are not stupid, and hooligans – absolutely not.

Perhaps the time is ripe for The EGAT and others in far-away Bangkok to climb down from their ivory tower and face realities and care a little less about losing face. Does anybody sincerely believe that old grannies will sit in the open, week after week, if they were not provoked and trod on by The EGAT officials? In a multi-billion baht project there also ought to be room for regards for the weakest.

I have lived long among these people and I have experienced much kindness among them. Above all things, I have found them exceedingly tolerant. Even in spite of what you read about the protesters, they are decent, not debauched. They are temperate even in their vices, moderate even in their licences. Such will they always remain in my memory.

Peder Jorgensen

Pibulmangsahan

Peder Jorgensen was a missionary based in Pibulmangsahan, Ubol, in 1990s and an eyewitness to a brutal treatment of men and women severely affected by the Moonmouth Dam, staging a sit-in campaign to ask for adequate compensation. Peder Jorgensen and his wife, Ruth, were no longer in Thailand after having witnessed the incident.

Power over the powerless

It appeared that 1994 was a year of increasing conflicts.

In that year, 200 dwellers in Sirindhorn District of Ubol convened for 10 days to make a plea for compensation for the distress and the losses they had been suffering from Sirindhorn Dam. The main damage was the flooding of their farms following its completion 20 years ago.

At the beginning, the Department of Energy, the initiator of Sirindhorn Dam, stated in 1971 that each of the families affected by the Dam would be given between seven and fifteen rais of land in compensation.

It turned out that some families did not receive any land. Those, who were relocated, found that the new locations were mostly infertile. Unable to produce sufficient crop for their consumption, a considerable number of the relocated people became beggars and migratory workers to survive.

In the 1970s the rural poor lived in fear of despotic authorities; none knew of human rights and had no strong leaders, no voice and bargaining power. As a result they made no demand, no plea for help and for fair compensation. Their silences satisfied the powerful bodies that suppressed the powerless people.

There was no organization to monitor and follow up compensation payments and other promises. The affected families accepted their sufferings as their fate and in silence while the province’s powerful logger benefited greatly from gaining concession to log the trees in the woods that surrounded the reservoir, which the Siridhorn Dam created after its completion.

Kaew Sukdi of Ban Nonchan lost 50 rais of arable paddy-fields without compensation. The alternative piece of land they could find to live on was suitable only for growing tapioca.

“Before, my family had enough rice to eat but we cannot grow rice on this land, and the price of tapioca is so low that we had to borrow money to buy rice,” he said.

Kaew Sukdi was an epitome of subjugated sufferers all over Isan. He simply uttered in his native tongue only when pressed to do so.

When the people, who had been affected by Sirindhorn Dam, heard that hundreds of the sufferers from the Moonmouth Dam gathered to plead for help and for fair compensation from The EGAT in early December 1994, they wanted to break their silence and voice the 20-year old grievances.

Hearing that a senior EGAT official would come to Ubol to listen to the complaint from the Moonmouth Dam sufferers, the Sirindhorn villagers gathered on 3rd December at Ban Lansawan and started their march to air their grievances to The EGAT as well.

On their way on the Pibulmangsahan-Chongmek Road a troop of riot police stopped them. At 1.30 p.m. that day, three fire-trucks jetted water at the marchers. Many fell down but they rose again, and once again they were struck down, but they managed to rise again and surged ahead to continue their march to meet the high ranking EGAT official.

When they reached Lamdomnoi Bridge at dusk, they found that the bridge was heavily defended by the police force.

As soon as it was dark, the attack began without any provocation from the marchers.

The squadron of 50 riot quenching policemen applied strong-arm tactics to disperse the straggling band of unarmed people some of whom were elderly women and pregnant women. More than 50 persons were seriously injured, particularly a Miss Aruni Singnont, who was kicked and stomped on by a policeman wearing combat boots.

Wittaya Yangmisuke, who suffered much from being bludgeoned, said:

”At least five policemen hit me, but I did not fight back. I just let them bash me till I fell.”

For almost half an hour, 12 battered elderly women crouched on the road, bending their heads low with their cupped hands touching their forehead in the manner of supplicating. They begged the 200 strong policemen for mercy and let them pass. But there was no mercy.

“The police kept hitting us, kicked and stomped on us while we were on the ground, pleading and wai-ing them,” said Somkid Boonthuk. “They did not spare even very old women.”

Among the badly injured, Buarian Sukdi from Ban Laemsawan was bashed on the head, chest and shoulders. On Pankam, who came from Ban Wangyang, was hit on the face, arms and chest so hard that she had difficulties in breathing, and several of her fingers were broken. One of her arms was badly bruised.

“The police force attacked us for half an hour though we did not fight back at all. All we did was begging them for mercy and for them to stop hurting us,” said Sak Sukdee.

Fourteen leaders of the march were arrested and put in jail.

None of the marchers reached the senior EGAT official, with whom they desperately wanted plead.

Desperation

Fifty-six year old Kanchanabury farmer Surin Surinkon had to seek some drastic measures to make his plight known to the authorities. His case was an eviction without compensation. Surin claimed that he and more than 6,000 families living in nine villages in Sankabury and Tongpapume districts had been unfairly evicted from their homes and farmlands when the Department of Forestry declared in March 1991 the 45,000 rais of their lands part of the newly-designated Khaolaem National Park in March 1991.

Surin Surinkon single-handedly made his grievance known, pleading with the government officials concerned to help make the Department of Forestry return the expropriated lands to the previous owners. When his plea for help went unheeded, he staged in front of the Government House a solo sit-in campaign that lasted several years.

During those years, he sought various measures to have attentions from the government. Such measures included a pleading letter written in blood and suicide attempts, ranging from drinking pesticide to cutting his throat and to hanging himself. But still the authorities from whom he sought help remained deaf and blind to his plea. In some quarters, the officials considered Surin mad.

As for Surin, being poor and uneducated, he had no other means to call for help from men in authority. His last resort was to barter his life for justice.

“I cannot live with dignity without a struggle for justice for me and 6,000 families that have been unjustly and brutally evicted from our ancestral lands on which we have lived and tilled for most of our lives,” said Surin, sitting inside the shelter made with a sheet of plastic tied to the trees on the pavement in front of Government House.

His protest continued from month to month and year to year, but to no avail. It lasted longer than the Chuan Leekpai government and the one that followed under the premiership of Banhan Silpa-acha, another failed administration. The lone protester had yet to wait for someone in authority in the succeeding government to hear him out and condescend to take some action.

“I have land title-deeds and other documents here in this file to back me up, but no one in authority wants to see them,” he said. “We live and toil on our lands a long time before the national park demarcation. Now our lands were needed for planting eucalyptus trees under the so-called reforestation scheme, so the authority concerned forced us to leave. When we refused they arrested us, claiming that we encroached on the national park, and put us in jail.”

The Department of Forestry had an approval from the Ministry of Agriculture to claim the people’s 45,000 rais of farmlands as part of a drive to achieve the target of increasing commercial forest lands to 40 per cent of the entire country’s area within five years.

Surin fought the charge in court and won, holding on to the legal document to prove his case.

“The judge ruled that we were not guilty, that we had the right to live and till our lands,” Surin said.

To prove his point, the lone protester displayed a copy of the court’s ruling which stipulated that the lands belong to Nikomsahakorn, the local cooperative estate, on which the inhabitants may live and toil on their lands, which had been excluded from the forest land status since 1975.

In all, Surin had submitted 27 petitions to three governments. The third administration was under the premiership of General Chavalit Yongchaiyuth.

“Writing the petitions for seven years, my hand writing has improved a lot,” said Surin. “Perhaps, it might be the only good thing that comes out of my struggle against the Department of Forestry.”

Prior to the preparation to commit suicide by hanging, Surin slashed his wrist and used a bowl to collect blood to paint his last petition on a banner. He managed to do the bold declaration that read: “With my blood and life I beg…” before a policeman stopped him to paint further.

Surin Surinkom had full support from his wife, Prapai, and their two daughters. “He will die for us and for other people, knowing that without the lands, we have no home, no work and no future,” she said.

Groups of villagers came and went to show their support at Surin’s campaign site. They believed that Surin’s death might be able to make the current government pay attention to their plight.

In January 1997, some 200 villagers from Khonkaen Province joined Surin Surinkom, airing their grievances brought about by the eviction from their holdings allocated as an industrial estate development and by the destruction of arable farmlands caused by toxic waste discharged by a pulp and paper mill in Nampong District.

It was considered that such large group of pleading people outside the Government House could have put the pressure on Interior Minister Sanoh Tiantong, who came out eventually to meet them.

His personal attention and a promise to appoint a committee to study their complaints, setting a 90-day limit to solve their problems, seemed to have pacified Surin Surinkom and the Khonkaen villagers gathering there. They dispersed eventually though there were fears that such promises might turn out to be empty as those given previously by other political leaders in other times.

Alas, Mr Sanoh Tiantong did not last long in office.

“As governments come and go, the same old problems escalate. Each year suffering people affected by land disputes, from the suppression of agricultural produce and from unfair evictions convene in Bangkok, seeking help from the government,” commented an observer. “Each year they return to their homes with promises that their trials and tribulations would be looked into, only to return to the capital in the following years to ask for assistance from the government which might not be of the same body of powerful men from whom the promises were given. The problem in Thai politics arises simply that the new group of ministers that replaces the ousted ones can be more avaricious, having awaited hungrily in the wilderness their turn to take power and to use their positions for their own gain instead of for the good of the country,” he said.

He went on to say: “All in all during my 50 years of observation, the only Thai leader who worked selflessly for the good of the country and its people is Chamlong Srimuang. But then he was in the way of the highly corrupt. He, like conservationist Kam Bootsi of Pakam District in Burirum, could not be spared. He had to leave the political arena altogether. Yes, you may say that he is lucky to be still alive. But in Thai politics, it is not far wrong to say that Chamlong has been ‘pickled’ so as to become politically inactive for the rest of his life, which is a kindness, considering over 100 conservationists, environmental activists, labour leaders and protesting farmers have been killed outright.”

Asked why certain eucalyptus plantation and pulp & paper company could blatantly encroach upon and took over vast areas of forest reserves with impunity, the observer said: “Some political leaders have vested interest in the corporations and companies concerned. One former minister of agriculture, for instance, became Chairman of such a corporation. Some of the former prime minister’s vested interests were in salt farming and in chemical producing companies including chlorine producing and supplying businesses. So the poor rice farmers whose rice fields were affected by the salt mining in the area could not possibly receive help from the Minister who later became Prime Minister when they lodged their complaint with him.”

However, that Prime Minister showed his true colour and eventually fell from grace and was replaced by another man, who, in turn, was ousted from the seat of power by another man. Then that successor to the high office was later dislodged from power. And then another man came along and ousted the predecessor and took over the premiership, only to lose to another man, who had been impatiently waiting in the wing, but consequently that man had been ousted in what was called ‘a bloodless coup’ in 2006 by an army that claimed to have had a support from higher power.

While the charade of changing seats went on, the poor and beleaguered villagers in their millions were awaiting a helping hand. When their plight increases as years go by, they resort to marching in their thousands to Bangkok to plead for help.

On 2nd November 1993 the number of Isan villagers marching towards Bangkok to air their grievances swelled to 20,000. On their way, they were stopped by a squadron of police force to prevent them from reaching the capital. This time their complaint was the suppression of farm produce such as rice, tapioca, cashew nuts and livestock. As opposed to the rising cost of commodities and the cost of living, prices of agricultural produce remained depressingly low. In fact they hardly had any increases in years. In some cases the prices of farm produce had been decreased and suppressed at a level that farmers had to sell their produce at a loss to earn some cash.

In early February 1994, some 2,000 aggrieved villagers from Konbury, Sikew and Soengsang districts of Nakorn Rajasima (Korat) heading for Bangkok to air their grievances were stopped by 300 members of the anti-riot policemen. Some 500 determined marchers managed to reach the Government House.

They wanted to plead to the government to look into the unfair and in some cases brutal evictions from their lands and the possibility of lifting the suppressed prices of their produce.

Urgent Social Issues

Since 1991, there was not a year went by without drastic social issues surfaced. The kingdom in conflict seemed like a body covered with boils that needed to be lanced and with the wounds that required medical treatments.

On the issues of agrarian conflict, Bangkok Post in its ‘Post Opinion’ column on 24th January 1995 remarked:

“Despite the fact that they form the majority of the population, the least privileged, the most tolerant, the toughest and the poorest of all the working people in this country, the farmers are still being treated with contempt as though they were second-class citizens. It is no wonder that whenever some farmers take to the street to voice their grievances, their move is certain to be viewed with deep distrust, especially by some senior government officials.

“The initial reactions by high-ranking officials of the Interior Ministry to a march to Bangkok of thousands of farmers from the Northeast to protest against the government’s alleged failure to fulfill its pledges given earlier clearly testify to their suspicion and negative attitude towards the dissenting farmers. “These people tend to draw attention to themselves once a year…” was a statement which reportedly came from the interior minister.

“Orders have been sent from the office of the interior minister to provincial governors in the Northeast instructing them to try to stop the protesting farmers from arriving in Bangkok. Veiled threats were also made against the farmers that they would be dealt with in accordance with the law if they block traffic or break the law during their protest.

“Officials of the Interior Ministry may feel nervous about the presence of a large number of disgruntled farmers in front of a government office, such as Government House because of the prospect of the protest getting blown out of control and posing a security threat if it drags on for a long time. This also applies to demonstrations held in front of Parliament. To a lesser degree, the protest may also aggravate Bangkok’s traffic gridlock.

“But had the officials shown understanding towards all the chronic problems confronted by the farmers and demonstrated more genuine concern for them, they would have shown more sympathy and less hostile attitude towards the protestors. In addition, they might have to thank the farmers for staging the protest to remind them of the promises given but which were broken intentionally or unintentionally.

“What’s wrong with the people who seem to be most admired for being the “backbone” of the nation but who appear to be the most exploited and least privileged so that they have to draw attention to themselves at least once a year? Is it not the duty and responsibility of the officials concerned and the Government to respond to their needs and problems?

“The farmers’ protest, which is led by the Assembly of Small-scale Farmers of the Northeast, should be viewed in more positive ways and in a broader perspective, especially by officials of the Interior Ministry. They are not trouble-makers as such, but desperate souls who are badly in need of help.

“Despite the fantastic export figures and the impressive economic growth rate that this administration is proud of and has taken the credit for, the majority of the farmers are still living below the poverty line. They have yet to benefit from the fruits of economic prosperity. Most are still trapped in the vicious circle of poverty and indebtedness as were their forefathers with little hope that their children will ever be able to break out of this entrapment.

“The protest will provide the leeway for the dissenting farmers to vent their anger and frustration. It would be very unwise and an invitation for trouble if any attempts are made on the part of the officials to resort to force to stop the farmers from arriving in Bangkok. A repeat of the Kamphaeng Phet tragedy in which a farmer was beaten to death during a protest must be avoided at all costs.

“Instead of sitting idly by and making noises in Bangkok, someone with decision-making authority should be sent to meet the farmers at their planned rendez-vous in Pak Chong district of Nakorn Ratchasima. Farmers may have a high degree of tolerance but their patience does have its limits, especially if pledges continue to be broken due mainly to insincerity and indifference on the part of the Government.”

Pollution

Similar to the drive to grow eucalyptus trees to cover 40 per cent of the total viable areas that the country has to offer, the thrust of industrial development has been taking its toll. The industrial pursuit in Isan is a clear case of the development that took priority over the livelihood of the populace and the ecology.

In March 1992, a case of severe pollution emerged. Isan’s two rivers, the Chee and the Nam Pong had been heavily polluted. Nam Pong River and Chee River join Moon River in Ubol. These three rivers are the main sources of water for millions of inhabitants in Khonkaen, Mahasarakam, Kalasin, Roi-et and Yasothorn provinces.

Nam Pong and Chee rivers had been polluted to such a degree that tens of thousands of dead fish cluttered the surface of the rivers, giving off foul smell. The water in the two rivers turned black, stank and became useless to men and animals.

Director-General of the Ministry of Industry’s Industrial Works Department, Pricha Atthawipat said on 30th March 1992 that the pollution of Nam Pong River and Chi River reached its peak in March, following a fire at a plywood factory, which is on a bank of Nam Pong. It was said that a large amount of water used in quenching the fire washed away toxic chemicals from bagasse which were raw material to produce plywood, stored at the factory.

However, Mr Pricha voiced that the severity of the pollution of the river could not possibly be from the toxic chemicals of one factory alone. Apart from toxic waste from Phoenix Pulp and Paper factory, he believed that the releases of 9,000 tons of concentrated molasses from the riverside Khonkaen Sugar Mill also took part in causing the astronomical level of water pollution. The two factories, standing side by side and owned by the Chin Dhammamitre Group continued to operate as usual after the pollution had been reported.

According to Pradit Polsaen, an officer of the Roi-et Provincial fisheries division, at least 30 species of the fish stock in the Chee River had been wiped out, and that it would take up to five years to recover.

To overcome water shortage among the inhabitants who had been relying on the water from the river, Yasothorn officials provided 31 water tankers to distribute water to the families which were severely hit by water shortage.

Korkiat Pukaothong, Chaiman of the Chee River Conservation Group, said the pollution had seriously affected farmers and fishermen who depend on the Chee River. He and his members were collecting signatures of the people affected by the pollution in preparation for making their complaint.

On 23rd June 1993, the local people were greatly disappointed by the provincial Attoney-General’s decision not to file criminal charges against any polluters of the Chee and the Nam Pong rivers.

The Attonrney-General’s office claimed that the discharge of molasses and toxic waste, including dioxin from the gigantic pulp and paper plant and from factories were unintentional. But the question in the people’s mind remained as to why the decision over whether the disaster was accidental or intentional or whether there was any negligence involved on the part of the polluters, was decided by the Attorney concerned and not by a court of law.

The decision of the Khonkaen Attorney-General’s office also demonstrates the inability of the public to bring charges against the polluters and to seek compensation for damages inflicted upon them as a consequence of pollution.

On this issue, Bangkok Post editorial remarked on 4th May 1993:

“The recent decision by the Khon Kaen provincial attorney-general’s office to drop criminal charges against Khon Kaen sugar mill and Phoenix Pulp and Paper, the two alleged polluters of the Nam Pong, Huey Jod, Chee and Moon rivers, is a big let-down for the people of Khon Kaen and the Fisheries Department, environmentalists and the public.

Criminal and civil lawsuits were brought against the two companies by the Fisheries Department. A separate civil suit was also filed against them by the Provincial Waterworks Authority. The litigation followed what was described as the country’s worst ecological disaster. The long-term ecological effects are yet to be evaluated.

Because of the immensity of the damage done to the ecological system and the hardship caused to the people whose livelihood depends on the rivers, it had been expected that retribution would be exacted from those responsible for the pollution.”

Such ‘retribution’ had not materialized. However, The Minister of the Ministry of Agriculture ordered Phoenix Pulp factory to close its operation for 30 days to ‘clarify the facts’.

An observer remarked that the minister took that action due to his favour given to Phoenix Pulp’s competitor, a eucalyptus plantation and pulp & paper concern of which he later became Chairman. Should the minister had been chairman of Phoenix Pulp, he would not order it to close down its operation even for one day.

On 30th May 1993, Bangkok Post observed: “Occasional factory closures, however, do not solve the conflict between the government’s desire for economic growth through foreign investment and environmental conservation and protection of people’s rights. Since the very beginning of industrial development here, the government has never been able to balance these two goals, and often it heavily favours development at the expense of the environment. For example, Phoenix Pulp and Paper has been granted promotional privileges by the Board of Investment (BoI) to run the pulp and paper business in Khon Kaen -- a 6,000 million baht investment. Despite its poor environmental record, the company is planning to open another factory by the middle of 1994.”

This worst environmental disaster directly hit over 400 rais of farmlands in close proximity of Huay Jode and Nam Pong River.

“Pheonix Pulp and Paper factory has dumped polluted waste water into Nam Pong River for a long time,” said academic Chutima Kukusamut of Khonkaen University’s Science Faculty. “It was an outstanding example of the mistake of past government policy which concentrated only on the promotion of investment regardless of environmental cost.”

In Khonkaen Province there had been an increasing number of factories, encouraged by the scheme to set up industrial estates. To cut costs and maximize profits, industrial entrepreneurs preferred to build factories on river banks due to the convenience of water supply and of discharging waste into the rivers.

Investing in waste treatment system was considered unnecessary and a cut into the profits while the government did not effectively enforce any environmental conservation measures.

Meanwhile, the people suffering from water pollution downstream wondered how the industrialists could build numerous large-scaled factories upstream. They did not know that factories such as Phoenix Pulp & Paper and others were given freedom to choose their locations under the governmental scheme of industrial investment promotion.

Successive governments have adhered to this policy and failed to see the damages to the environment and the harm it has brought to the multitude of people. As long as their purposes are met, they can ignore the rights of the people in stead of establishing measures and strictly enforce those measures on the entrepreneurs so as to curb the pollution.

While the environmentalists and conservationists were concentrating on the issues of water pollution, someone should give attention to the air pollution that pulp and paper mills could cause.

According to a research made by Ricardo Carrere and Larry Lohmann for their book, Pulping the South, Industrial Tree Plantations & The World Paper Economy, ”…between one to three kilogrammes of sulphur dioxide are released to the air for each tonne of pulp produced, with potential effects on soil, water, and the health of humans and plants.

“The sulphite process boils wood chips in an acid solution, yielding a light brown, strong, soft pulp. The sulphite process also reuses chemicals, but emits more, around five kilogrammes of sulphur dioxide per tonne of pulp, and the damage caused over the past century by the water pollution associated with this process is inestimable. As with the sulphate process, cellulose fibres lost during processing are discharged into waste water, where they decompose, depleting the oxygen dissolved in the water.

“The chemo-thermi-mechanical process also discharges chemicals removed from the pulp but also the sulphur added in the pulping process, creating a highly-toxic, persistent effluent.

“Papers produced by either mechanical or chemical processes require bleaching. Yellow mechanical pulps are usually bleached with hydrogen peroxide, while dark brown kraft pulp requires heavier bleaching, traditionally with chlorine or chlorine dioxide, but now, increasingly – as a result of environmentalist campaigns and consumer pressure – with oxygen, ozone or hydrogen peroxide. Chlorine and chlorine dioxide, while they are effective in removing lignin and in strengthening pulp, react with organic chemicals present in pulp to form hundreds of organic-chlorine pollutants including dioxins, which are some of the most potent poisons known.”

Due to these known facts, pulp and paper factories are to be found more and more in third world countries where environmental measures are still lax or non-existent. Where, in some third world countries, industrialists are required to invest at least five per cent of their investment on ecological conservation measures, they invested less than three per cent on pollution control.

Another controversial ‘project’ to watch is potash mining in Udon Province. In March 2003, Senator Kaewsan Atipo, a member of the Senate Environmental Committee, commented that the Office of Environmental Policy and Planning Authority should be sued for approving the ‘unsustainable’ studies of the environmental impact of potash mining project in Udon.

“The Canadian-owned Asia Pacific Potash Company, the project developer, should come up with a better Environment Impact Assessment (EIA), if it would win a 22-year concession,” Senator Kaewsan stated at a seminar on experts’ studies on the potash mining project on 29th March.

On the outset, local inhabitants have already begun to oppose the company since the company’s assessment study of impact on the environment failed to convince geologists, engineers, and scholars in the area of safeguarding the ecology against pollution and soil subsidence.

Somkiat Putongchairit, deputy director of the Primary Industries and Mines Department admitted that the company’s EIA had flaws and ambiguities, that its pollution control measures stated were mere concepts without concrete back-up or evidence.

The project to mine potash to make fertilizer is supposed to be carried out underground in a 25 square kilometer area. Without effective environmental control measures, the project could release daily 10 tonnes of salt dust into the air. Besides, a huge pile of salty potash by-product, as high as a 16-storeyed building, might affect the ecology, if the substance found the way into the river that flows downstream into Nong Han Reservoir.

The Dying Earth

Underneath the topsoil in various parts of Isan, particularly in the districts of Korat, Mahasarakarm, Roi-et, and Sakon Nakhon, lies a vast wealth of salt deposits.

The increasing demand for industrial salt has made investors, some of whom are prominent politicians (one of whom was a prime minister), invest in salt mining in Isan. Industrial salt is used in producing wide range of products including plastics, chlorine, batteries, corrugated iron, dyes, freon and glass.

Whether it is by intention or negligence, the salt waste and brackish water from industrial salt mines flow into the nearby canals, rivers and paddy-fields, killing aquatic life, vegetation and rice.

The damages to the ecology from salt mining prompted suffering villagers to group and rise in protest when several complaints lodged with authorities were to no avail.

On 10th April 1990, about 1,000 affected villagers from 50 villages from Wapipatume and Borabue districts of Mahasarakarm, Pratume Ratana, Kasetwisai and Suwanapume of Roi-et Province and Rasisalai of Sisaket Province marched to air their grievances to the authorities at Wapipatume District Office.

Among the requests the suffering people wanted the authorities to deal with is to revive the severely polluted water in Siawyai River to a level that the people could once more rely on it for food and cultivation.

Kamnak Wangkong, headman of Ban Kaem in Wapipatume District said that 200 families in his village suffered from brackish water from Siawyai River. For a start they could not grow rice on their affected paddies and could not catch fish in Siawyai River since all aquatic life in it had perished. The culprits were the polluters who, since 1971, mined more than 2,000 rais of lands near Nong Bo reservoir in Borabue for industrial salt.

Siawyai River winds over 225 kilometres from Nong Bo Reservoir in Borabue District of Mahasarakarm, a lifeline of more than 500 communities in eight districts, to join Moon River in Sisaket. Its water, contaminated with brackish water discharged from various salt mines upstream, affected at least 500,000 human beings, not counting the heads of cattle and herds of buffaloes that rely on the water from Siawyai River for survival.

While the suffering people were rallying to make their grievances known in front of Wapipatume District Office, an anti-riot team of police force applied violence to subjugate the revolting villagers who were seen as mobsters and trouble-makers. The force beat and battered and arrested the marchers until there was no room in jail to confine them.

A foreigner, an eyewitness to the brutal treatment of suffering villagers, claimed that a policeman had snatched his camera and destroyed the film of which he photographed the scene of violence.

But quenching unarmed complaint makers with violence could not solve the conflict. In January 1993, more than 30,000 inhabitants hard hit by salt mining in Sakonnakorn Province rose in protest against the polluters who polluted their rice fields, canals and killed aquatic life, their source of food.

Champa Suwantrai, a medic from Tambon Muang, asserted that canals in Ban Huaybodaeng and Ban Huaysang became so salty that the waters were not fit for use and consumption for men and animals.

The two biggest clients of the industrial salt mines in Isan are Saha Srichai Chemicals and Thai-Asahi Soda. According to Khao Piset Magazine, the major shareholders of both companies are leaders of the Chart Thai Party (one of whom was the Minister of Ministry of Interior at the time of conflicts and later became Prime Minister) and several influential families which control diversified businesses in Thailand. Their names are listed in an article ‘The White Gold’ Rush by Sanitsuda Ekachai, in Bangkok Post, 28th June 1990.

Death to Environmentalists

Out of over 100 deaths of environmentalists, conservationists, and graft-fighters, at the hands of hired gunmen, the following cases are cited as examples of the use of a deadly but inexpensive measure to ‘liquidate’ opponents who dare to challenge the powerful.

The killing of Samnao Sisongkram in Khonkaen

In May 2003, Samnao Sisongkram was shot dead by a gunman at his home in Khonkaen Province. Samnao, 38, head of Nam Pong River Conservation and Revival Group, was in the throes of leading villagers to protest against the Phoenix Pulp & Paper Company which has been polluting the Pong River since 1993.

Three days before the murder took place, Samnao had several threatening telephone calls from men who claimed to be Phoenix Pulp and Paper Company’s representatives.